Grading…what a beast! It is an immense and complex topic that touches on learner motivation, what it means to be a good teacher, and everything in between.

What do I want for my students?

(What I wish for that is mostly under their control)

- To take a risk, to step out of their comfort zone

- In learning a new subject that they had negative inclinations toward or had no idea about. In letting themselves be vulnerable enough to be curious.

- In connecting with others whom they might be unsure about. To be curious about the life of someone who they would probably not connect with normally.

- To experience some joy and curiosity about data and statistics

How do the different parts of my grading system incentivize or disincentivize these?

What do I want for myself as a teacher?

(What I wish for that is mostly under my control)

- To connect authentically with my students - where that connection is over ideas both related to and unrelated to the course.

- To value my feedback and use it to improve

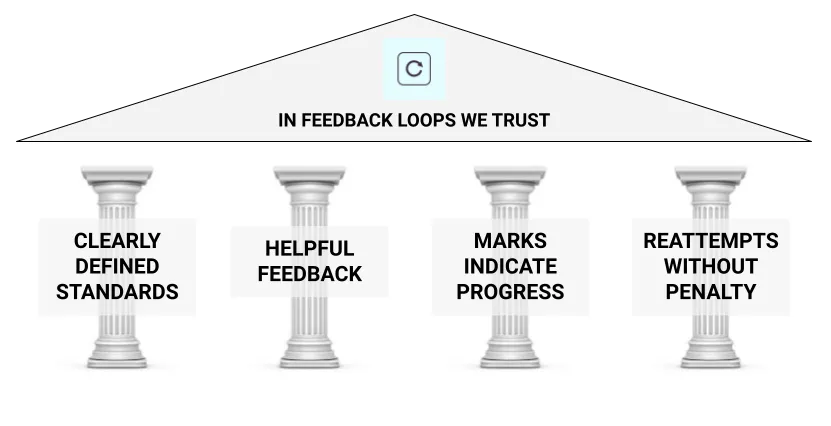

The 4 pillars of alternative grading

Robert Talbert and David Clark from the Grading for Growth blog propose these pillars in this post:

Clearly defined standards

It’s hard to disagree with this one. Having a set of clearly defined standards is useful for both students and the instructor.

- For the instructor, it gives clarity on the vision for the course.

- For the student, it gives clarity on where to focus their efforts and what the big picture is. Reviewing the course learning objectives as a whole can help students

This reminds me of a moment during the Johns Hopkins Summer Teaching Institute. We were learning about course-level learning objectives and lesson-level learning objectives, and they were saying that lesson-level learning objectives needed to be written in an action-verb oriented way to be assessable. I asked if course-level learning objectives needed to be assessable too. The workshop leaders said, “No, they’re just for guiding the focus of the course.” While I agree that course-level objectives are useful for that purpose, why can’t they be part of an assignment that gets assessed?

Assignment Idea

Have students review the course-level and lesson-level learning objectives at the end of the semester and explain how the lesson-level objectives link to the course-level objectives.

Helpful feedback

Fully on board with this one. Qualitative feedback is my preferred method. I found these insights from the Feedback in Small Shifts session at Macalester’s 2023 Spring Professional Activities Workshop were particularly helpful in my perspectives on feedback.

Marks indicate progress

In this post, Robert Talbert digs into this pillar more. After reflecting on ungrading and the benefits of qualitative feedback, Robert adds this caveat:

So interpret the third pillar as If you give marks at all, they should indicate progress.

In my Spring 2024 Epidemiology course, I used a 3 mark scale for individual homework problems: fully correct / mostly correct with minor errors / revision encouraged. Each problem was given one of these 3 marks by my preceptors. If a student received a revision encouraged on any of the problems, they would earn a Not Yet mark on the homework. Otherwise (for any combination of fully correct and mostly correct with minor errors) they earned a Pass on the homework.

I absolutely did not have the time to read all of my students’ homework, so I had to trust that my preceptors were doing a good job. From glancing at their comments and marks, I was generally ok with their feedback. But I did get feedback from one student in my course evaluation that this 3 mark system combined with the Pass / Not Yet mark on the homework didn’t motivate them to look carefully at problems that were mostly correct with minor errors if they received a Pass overall. Totally fair.

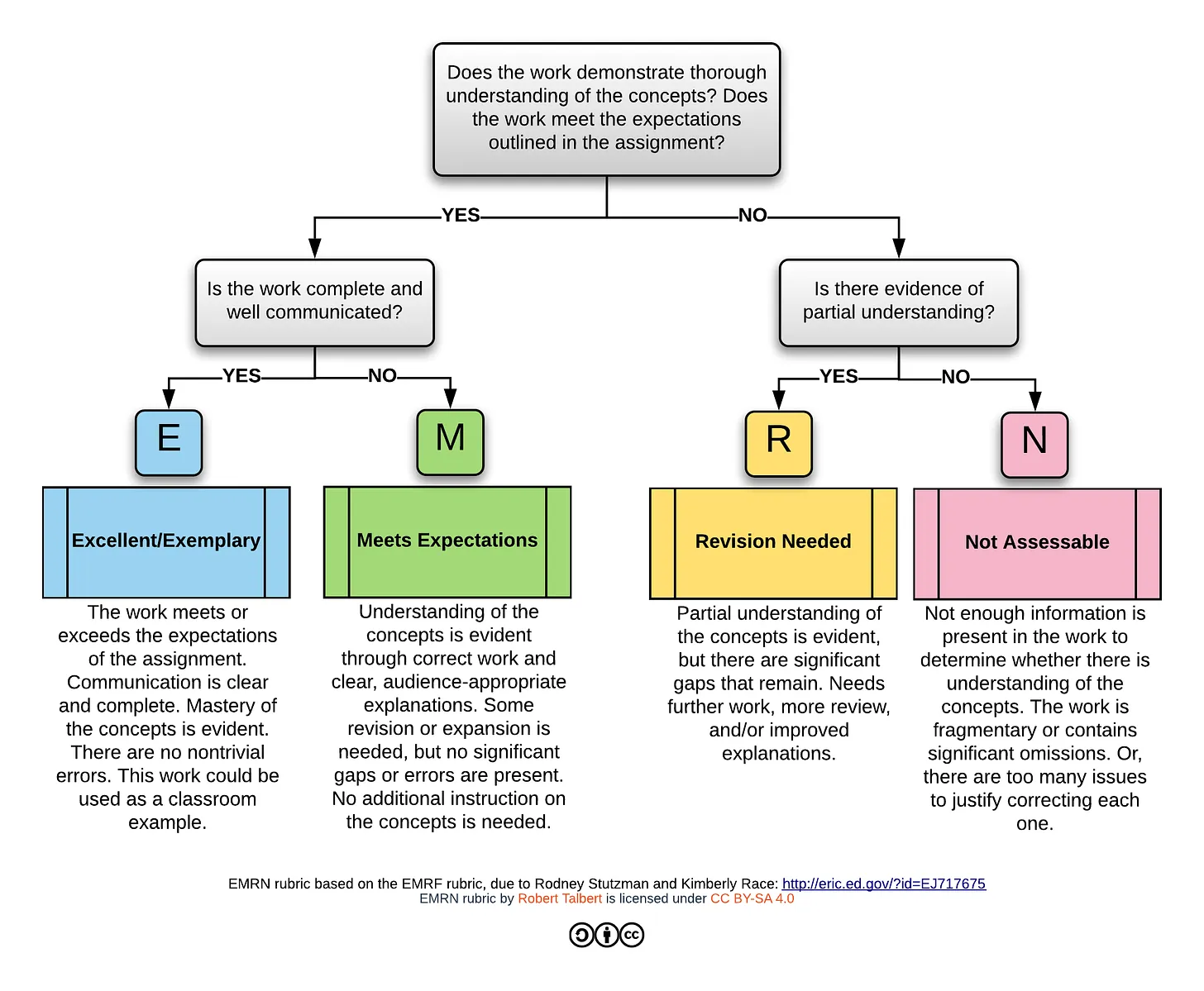

When I taught Machine Learning in the module system, I gave take-home quizzes that were on a 4 point scale, which was a lot like Robert Talbert’s EMRN rubric:

Reattempts without penalty

This has been a mainstay in my grading systems ever since I started experimenting with alternative grading.

I do want to note that “reattempts without penalty” means “reattempts without direct penalty on your grade” and NOT “reattempts without constraints”. Because the reality is that the instructional team absolutely has constraints on their time. These constraints might make it so that a student is not able to demonstrate the highest level of understanding within the reattempts that the instructional team has time for.

From Robert’s post:

Does allowing reattempts without penalty lead to grade inflation? Not really. “Grade inflation” refers to increases in grade levels without a corresponding increase in the quality of the work. That second part is key; simply having higher grades by itself isn’t grade inflation. Reassessments let students demonstrate that they have actually learned. When we allow reassessments without penalty, grades do tend to increase, but they are tied to concrete evidence of improvements in learning. This isn’t “inflation” — it’s accuracy, and validity.

But I do want to stress that “reassessments without penalty” does not mean reassessment without responsibility. While we shouldn’t penalize growth, we can design our courses so that students don’t take the reassessment opportunities the wrong way.

Instead of penalizing, you can place reasonable limits on reassessment opportunities.

We can limit the number, schedule, and frequency (e.g., one problem per week) or reassessments.

The 3 pillars of equitable grading

In his book Grading for Equity, Joe Feldman proposes 3 pillars for using grading to promote equitable learning experiences for students. Grades should be:

- Accurate

- Bias-resistant

- Motivational

What is the point of grading?

What Does an A Really Mean? from The Chronicle of Higher Education offers several perspectives on what grades mean to students, teachers, and the world beyond college.

Grading generally has the following intents and impacts. Whether these intents and impacts are good is another question.

- Give feedback to students during a course

- Encourage students to adopt certain behaviors (which may or may not be learning-supporting)

- Signal to students whether they are good at something

- Signal to those outside of college what a student knows

If we accept that learning and feedback is where teachers start when thinking about their grading systems, we still have to be wary of a slippery slope when it comes to assessment. Often, the picture can look like this: Assessing → Measuring → Ranking → Dividing → Norming → Removing/Culling. When we slide down the slope towards ranking, dividing, and norming, we run the risk of culling people who are deemed “unfit” by the measure that we choose (whatever grading system we implement). How can we prioritize welcoming in and back instead of weeding out? (Perspective comes from Sarah Silverman’s session at the 2024 Grading Conference.)

Making disciplinary practices an explicit part of the grading system

(Thanks to Amy Parrott and Jason K. Belnap for facilitating this session at the 2024 Grading Conference.)

Motivating question: How does the work and focus in your discipline compare to the K-12 student experience? Undergraduate experience? Public perception?

How do K-12 students, undergraduate students, and the public perceive statistics? My impression is that statistics is perceived as rote, boring, useless in daily life, and untrustworthy.

The motivating question is meant to highlight the differences between how we actually practice our disciplines and what others perceive. Disciplinary practices are the subtle parts of our disciplines that permeate the day to day. But they need not be subtle in our classrooms!

What practices do I want my statistics and data science students to develop?

- Curiosity: Experiencing the tug of an interesting question and following it on paths shaped by data

- Concern for others: Statistics and data science truly are tools to help make the world a better place. They are absolutely not the only tools, but they are tools that are part of an approach.

- Humility: Like any tools, statistics and data science are not perfect for learning what we need to about the world.

Small micro-practices that students can practice regularly to engage in curiosity, concern for others, and humility can be part of the course grading system.

Ungrading and motivation

(Thanks to Ashleigh Fox for facilitating this session at the 2024 Grading Conference.)

Ungrading has the following benefits for student motivation:

- The emphasis on reflection and conversation with the instructor to assess learning shifts the focus from grades to learning.

- Ungrading appears to increase autonomy and, in turn, intrinsic motivation.

- Ungrading appears to reduce student incentive to engage in academic dishonesty.

- Ungrading can really foster a growth mindset by not only destigmatizing failure but embracing it as a crucial part of the learning process.

Ungrading can also be a barrier to student motivation:

- The science of negativity bias tells us that humans have a biological inclination to allocate attention toward potential threats instead of positive information. This results in a decrease in motivation when punishment is removed. When an incentive is framed as an avenue to acquire something instead of to prevent the loss of something, individuals exhibit lower levels of motivation

- Students may pay more attention to positive feedback that tells them where they’re already doing well than negative feedback that tells them where they can keep improving. This means that they may not fully engage in learning feedback loops.

- Simply removing grades doesn’t increase motivation to learn.

- Students don’t always take advantage of opportunities to revise/resubmit work.